How Our Brains Age: A Look at Cognitive Peaks and Decline

Exploring how cognitive abilities change with age, from childhood peaks to midlife shifts and beyond.

Cognitive Ageing is Not Uniform: Cognitive decline varies across individuals and functions; some abilities peak early and gradually decline, while others improve or stabilise over time.

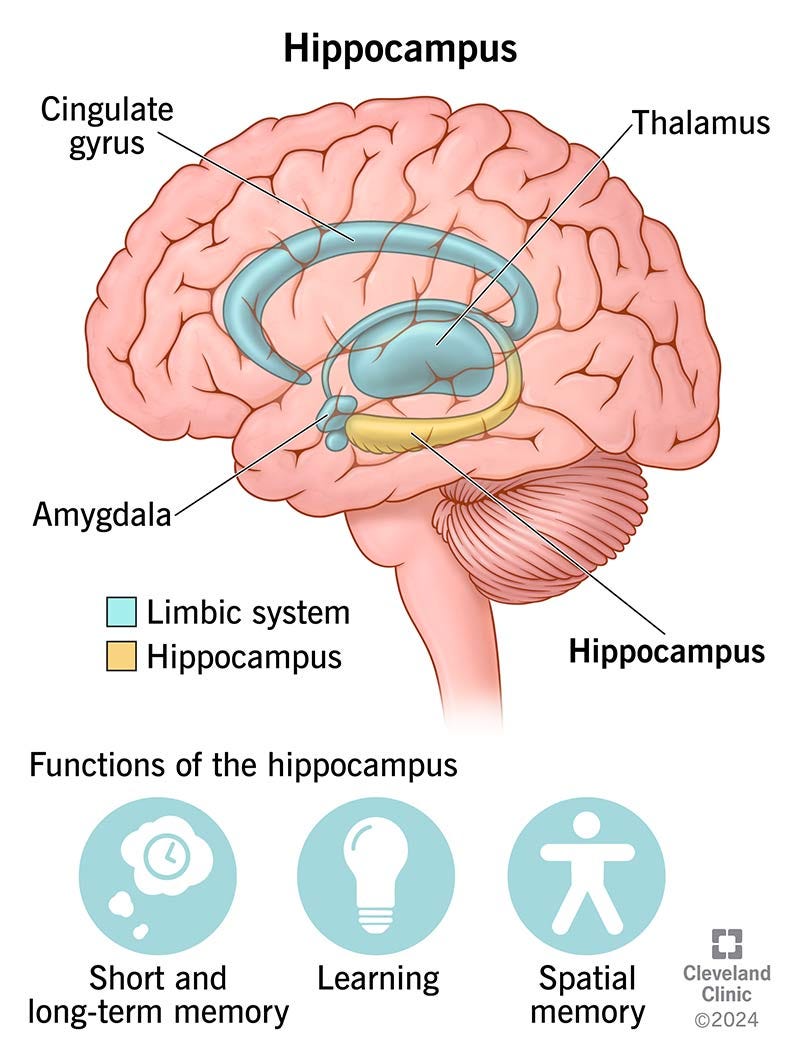

Brain Development in Early Life (0-18): The brain undergoes significant growth during early years, with different regions developing at different rates, such as the hippocampus by age 5 and the frontal lobe into the 20s.

Peak Cognitive Abilities (18-35): Mental processing speed, attention, and working memory reach their peak in the 20s and 30s, but minor declines can start around age 25, particularly in working memory.

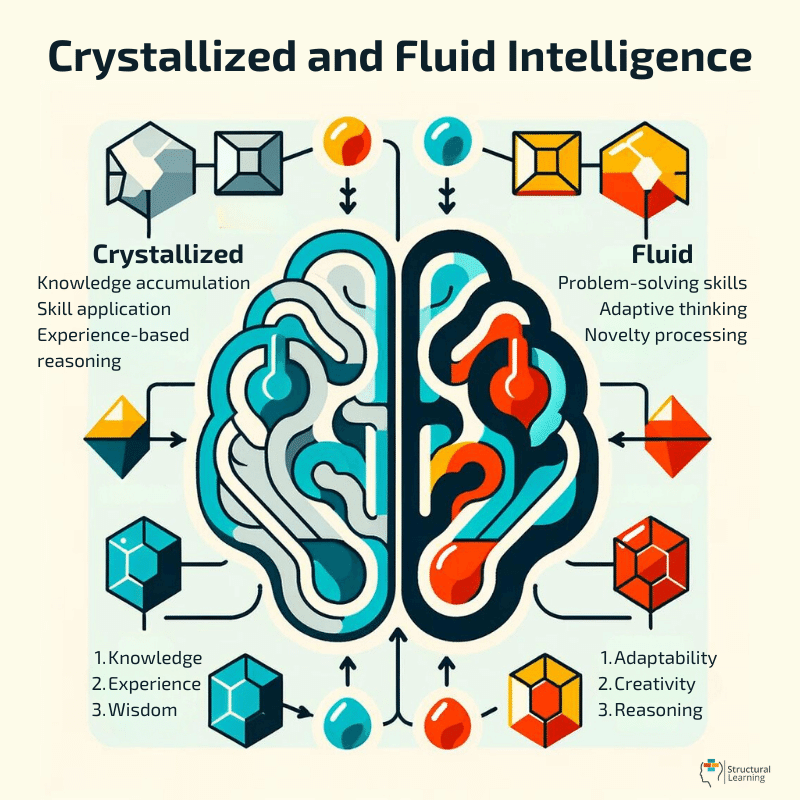

Midlife (35-55): While processing speed and memory may decline, “crystallised” abilities such as vocabulary, street smarts, and decision-making continue to grow and can offset declines in other areas.

Later Years (55+): Cognitive declines accelerate after 50, especially in declarative memory, but crystallised knowledge such as wisdom and vocabulary remain valuable strengths.

Ageing Variability (65+): Cognitive changes become more varied in older age. Episodic memory - memories of specific events - may fade, but deeply-encoded memories from early life can remain vivid.

How cognitive abilities change with age and what it means for us all?

Cognitive aging is not a straightforward decline, as often perceived. According to Elana Spivack’s article in Inverse, scientific research shows that cognitive decline varies significantly among individuals and is influenced by numerous factors. This insight challenges popular views on aging, particularly in political discourse, where cognitive abilities of aging leaders are frequently scrutinised. Cognitive scientists, however, affirm that ageing and cognition do not follow a uniform path, and each person experiences cognitive changes in unique ways.

Ana Daugherty, a cognitive neuroscientist at Wayne State University, emphasises that cognitive ageing is an emerging research area with substantial unknowns, and that decline does not necessarily imply a rapid descent into dementia. According to Daugherty, "there is just so much that we still do not know,” indicating the complexity of cognitive aging.

Early Development: Ages 0 to 18

During childhood and adolescence, the brain undergoes significant growth and development, reaching various maturity levels at different ages. The hippocampus, a brain structure crucial to memory, typically completes its development by age four or five, while the frontal lobe, which governs reasoning and decision-making, continues to mature into the mid-twenties. This period is marked by “florid growth,” as Daugherty puts it, where the brain’s networks strengthen and solidify, laying the foundation for cognitive abilities.

Annalise Rahman-Filipiak, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan, refers to this process as the differentiation and dedifferentiation hypothesis, where cognitive abilities gradually become more specific. This phase concludes around age 18, yet the brain remains unfinished, contrary to the assumption that human brains peak by adulthood.

The Peak of Cognitive Abilities: Ages 18 to 35

From early adulthood into the mid-thirties, some cognitive abilities, such as attention and processing speed, reach their highest levels. Rahman-Filipiak notes that “our attention, our speed of thinking, our processing speed” are strongest in our twenties and early thirties. This period also marks the start of subtle changes in brain function, with working memory - a core aspect of executive function - beginning to decline around age 25. This gradual decrease, however, is not usually noticeable in everyday life. As Spivack observes, it may manifest in small ways, like occasionally misplacing items, but overall cognitive abilities remain robust.

Middle Age: Ages 35 to 55

By midlife, a mix of both decline and stability is present. Although certain cognitive functions, termed fluid abilities (such as memory and processing speed), continue to decline, crystallised abilities like vocabulary, wisdom, and street smarts accumulate. Daugherty explains that while working memory and processing speed might weaken, vocabulary often peaks around age 50. This era highlights the balance between cognitive growth and loss, as one’s cumulative life experiences and knowledge can offset certain declines in function.

Middle age is also the time when lifestyle choices exert a considerable influence on cognitive aging. Conditions like high blood pressure and cholesterol, known risk factors for heart disease, have also been linked to cognitive decline. The choices one makes regarding diet, exercise, and mental activity can therefore play a significant role in the quality of cognitive aging.

Late Middle Age to Early Senior Years: Ages 55 to 65

As people approach their late fifties, the accumulation of gradual cognitive decline begins to accelerate. Daugherty notes that “after age 50 is when we start to see the acceleration towards meaningful impairments.” While such decline is natural and not indicative of dementia, it can affect areas like declarative memory - the “when, what, where” facts of life. This age-related memory impairment is common and often misinterpreted as a more serious condition, although it remains within the bounds of typical aging.

Crystallised abilities, however, continue to develop, underscoring the notion that while memory retrieval may weaken, accumulated wisdom and knowledge remain assets. Daugherty calls this a “mixed bag” of aging: even as some functions decline, others, such as decision-making and interpersonal skills, often remain strong.

Senior Years: Age 65 and Beyond

By the time individuals enter their senior years, cognitive abilities can diverge widely among individuals. Some people begin to experience noticeable cognitive effects in their fifties, while others maintain sharp cognitive skills well into their seventies. This variability underlines the uniqueness of cognitive aging, with executive functions - such as planning and decision-making, becoming more challenging for many seniors. Episodic memory, which includes specific past events, may also decline, particularly in the ability to form new episodic memories after age 65.

Rahman-Filipiak highlights the “temporal gradient of episodic memory,” a phenomenon where memories from early life are often better preserved than recent memories. This effect occurs because earlier memories are frequently revisited over the years, which helps them remain intact.

Cognitive Aging in Perspective

Understanding these patterns of cognitive aging could reshape our perceptions of aging leaders and the general population alike. The effects of aging are diverse, often unpredictable, and greatly influenced by lifestyle factors. Cognitive scientists like Rahman-Filipiak and Daugherty suggest viewing cognitive decline as a natural aspect of life, reminding us to approach both ourselves and others with compassion as we age. Rather than a complete descent, cognitive aging is more accurately a balance of gains and losses, where accumulated knowledge and skills coexist with changes in memory and speed of processing.